News

» Go to news mainWhen "forever" fades but the ink stays: PhD student develops new tattoo removal technology

It’s an all-too-familiar story: You meet someone. You fall in love. You show your love by getting your partner’s name tattooed on your arm. A few months or years later, your partner leaves — but your broken love remains forever inked on your bicep.

Tattoos are more popular than ever these days, which surely means more people walking around with ink that symbolizes a love — or some youthful interest or indiscretion — that is no longer.

If this story sounds like one you recognize, meet Alec Falkenham, a PhD student in Pathology at Dalhousie. His technology may be the answer you’re looking for.

A new approach for tattoo removal

Tattoo removal is big business — more than $75 million in the U.S. alone — and typically involves lasers that break down the ink particles in the tattoo, which is then absorbed into the body.

Falkenham has come up with a different approach, one that makes use of the natural healing process that your skin activates after it’s tattooed in the first place.

When you get a tattoo, the pigment from the ink deposits into the skin where it’s then consumed by white blood cells named “macrophages.”

“Macrophages are known as the big eaters of the immune system,” says Falkenham. “They eat foreign material, like tattoo pigment, to protect the surrounding tissue.”

In the case of tattoos, two populations of macrophages react to the ink in different ways. One set of macrophages transports some of the pigment to the draining lymph nodes, removing it from the area. The other population that has “eaten” the pigment goes deeper into your skin, becomes inactive and forms the visible tattoo. Over time, the macrophages that formed the tattoo are replaced by new macrophages, which cause the tattoo to blur and fade.

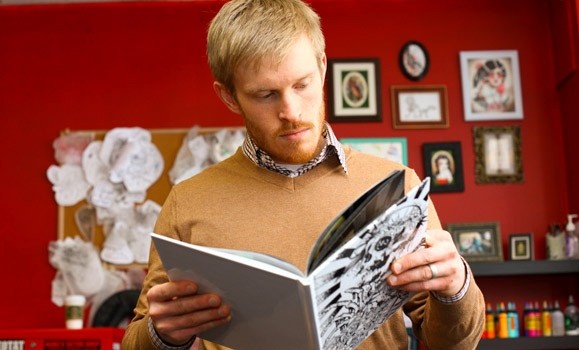

Falkenham at Halifax's Brass Anchor tattoo parlour.

Falkenham at Halifax's Brass Anchor tattoo parlour.

Targeting the “big eaters”

Falkenham’s technology, Bisphosphonate Liposomal Tattoo Removal (BLTR), targets the macrophages that contain the pigment for removal.

“BLTR is a cream that you put on your skin,” he explains, describing how BLTR makes use of a lipid-vesicle, or liposome, that his team has created.

“When new macrophages come to remove the liposome from cells that once contained pigment, they also take the pigment with them to the lymph nodes, resulting in a fading tattoo,” says Falkenham.

The BLTR technology is a safer alternative than current tattoo removal processes such as lasers. By acting as a “Trojan horse” in their drug delivery, liposomes target cells that can consume them, specifically those that contain pigment. This limits potential side effects to the small number of surrounding cells that do not contain pigment.

Closer to erasing your ink

Falkenham worked with Dal’s Industry Liaison and Innovation (ILI) office to patent his technology. Together they have secured funding through Springboard Atlantic and Innovacorp Early Stage Commercialization Fund for his research into BLTR and he is continuing to work with ILI.

“Alec is a trail blazer in tattoo removal – he came to ILI with an idea, tangentially related to his graduate research, that had real-life applicability,” says Andrea McCormick, manager, health and life sciences at ILI. “His initial research has shown great results and his next stage of research will build on those results, developing his technology into a product that can eventually be brought to market.”

So does the guy who has developed technology to remove tattoos have any tattoo regrets of his own?

“This idea started when I got my first tattoo and I was thinking of the tattoo process from an immune point of view,” explains Alec. “Since then, I have added three more and currently don’t regret any of them — but that’s probably a reflection on me waiting until I was older.”

Recent News

- Dal researchers unite to help tackle high epilepsy rates in remote Zambia

- Second year medical student catches attention of top morning show

- Celebrating 10 Years of Dalhousie’s Medical Sciences program

- Global impact: Three Dal faculty recognized in 2024 Highly Cited Researchers list

- Student offers simple skills on how to quickly improve care for people with sight loss

- Three Dal researchers nominated for this year's Public Impact Award

- Dal student triumphs at Falling Walls in Berlin

- One in five kids endure chronic pain. A new pain standard will soothe it