» Go to news main

Dal Med Innovator | Dr. Chester Stewart

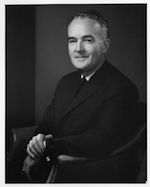

Dr. Chester Stewart, the visionary dean who modernized the medical school

Dr. Chester Stewart, the visionary dean who modernized the medical school

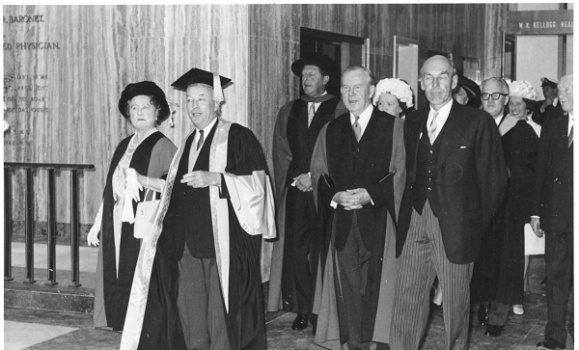

Chester Stewart came to Dalhousie Medical School in 1934, when its founding was still within living memory. The relatively young school was, like the relatively young nation, trying to keep pace with the rapid changes of the 20th century. But Chester Stewart—shrewd, determined, and visionary—was the right person for the medical school in the era that followed. As dean from 1954 to 1971, he transformed Dalhousie Medical School into the modern institution we know today.

Born in Norboro, PEI, Stewart was an outstanding student at Prince of Wales College, but left early to work as a teacher and vice-principal of Kingston High School. When he returned to college, he finished as top student in his class. The accomplishment earned him a gold medal, which he promptly pawned to pay for medical school.

To say Stewart was an outstanding student at Dalhousie would be an understatement, as he finished with distinction in 31 out of 33 courses. After graduating in 1938, he worked as assistant to Sir Fredrick Banting of insulin fame, assessing medical research in Canadian medical schools. He was primary author of the first comprehensive report on the state of medical research and training in Canada.

At the outbreak of WWII, Dr. Stewart was commissioned lieutenant (later promoted to wing commander) in the RCAF Medical Corps, where he led four aviation medicine research units over five years. Closer to the end of the war, then-dean-of-medicine Dr. Harry Grant offered him a chair in epidemiology at Dalhousie, which he accepted on the condition that he be able to complete his Masters of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University first.

Dr. Stewart took up his professorship at Dalhousie Medical School in 1946, and began a decades-long involvement in shaping the national debate around what the Canadian health care system would look like in the latter half of the 20th century.

He obviously made an impression at the university, because Dalhousie President A.E. Kerr offered him the role of assistant dean in 1952. Much to Kerr’s surprise, he refused.

According to former Dal Med dean, Dr. Jock Murray, who writes about Chester Stewart at length in his 2017 book, Noble Goals, Dedicated Doctors: The Story of Dalhousie Medical School, he believed the medical school needed major changes and that he would need a stronger negotiating position—such as the deanship—to achieve them. Dean Grant was set to retire in 1954 and, just before midnight on New Year’s Eve 1953, the president called Stewart to offer him the job. Stewart presented a list of conditions, which Kerr refused. Stewart held his ground and eventually the president acceded. Dr. Stewart was now Dean Stewart, with power over appointments, professors’ salaries and day-to-day operations. The power, in short, to remake Dalhousie Medical School.

Dr. Stewart could see the future. He knew from his committee involvement that Canada was headed toward a national system of health care and the time to prepare was now. He began by building a stronger academic foundation with eight key new appointments. By the time he stepped down in 1971, he had increased the number of appointments in the medical school from 16 to 160. During his first few years he also began pushing for larger classes. In 1960, the medical school was graduating only 55 students a year. Dean Stewart wanted it boosted to 100 and was largely successful… in 1968, 96 students started first-year medicine at Dal

He was also ahead of his time on issues of social equality. Before his tenure as dean, he co-authored a report noting the disparity in access to doctors between wealthy and low-income families. Later, during his push to increase class size, he made it a priority to recruit students from all walks of life, pointing out that, in 1961, doctors were only 0.2 per cent of the general population, but 18.9 per cent of Dal Med students had physician parents.

Dean Stewart pushed relentlessly for change on many fronts—sometimes fighting the faculty, as when the old guard resisted curricular reform, and sometimes fighting the university leadership for research dollars or faculty salaries. Up until the 1960s, for example, professors taught as volunteers and internships at hospitals were informal. Eventually, Dean Stewart forged formal internship arrangements and, in 1962, instituted a policy of recruiting professors to paid positions—selected specifically because they were good teachers, not just good clinicians or researchers. This reflected the vision he set for the school in 1955, when he added the Old Scottish motto, “Ilk ane to instrict vtheris”—each one is to instruct the others—to the school emblem.

Research was also a priority for Dean Stewart who, ever ahead of the curve, went to President Kerr in 1961 with the idea of a new medical school building as Nova Scotia’s Centennial project. He was shrewd in his suggestion of “the Sir Charles Tupper Medical Building,” as Tupper was a driving force behind the founding of the medical school and the nation. With the opening of this building, Dalhousie Medical School was now equipped with some of the finest medical research labs in Canada.

“Dr. Stewart knew people thought the Tupper building was his greatest contribution,” says Dr. Murray. “But he was most proud of the changes he helped bring about in the education of medical students, the growth of the budget and research grants and the overall improvement of Dalhousie’s standing as a medical school.”

Chester Stewart made a huge impact at the national level, too. As president of the Association of Canadian Medical Colleges, he successfully lobbied the Hall Commission for a health resources fund that assisted the growth of all medical schools across Canada. As Chair of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada’s Specialty Committee for Public Health, he established public health as a Royal College specialty. Both of these accomplishments were cited in his Duncan Graham Award of the Royal College in 1996.

When Dr. Stewart stepped down from the deanship 1971, the role passed to Dr. Lloyd B. MacPherson. He inherited an institution that would have been unrecognizable to the young Chester Stewart, arriving from PEI in 1934. At a gala dinner in Dean Stewart’s honour, it was announced that the gold medal given at graduation would be named the C.B. Stewart Gold Medal. A fine return on the investment, in the end, for the one he pawned to get into Dalhousie in the first place.

Many thanks to Dr. Jock Murray for allowing Dalhousie Medical School to use his book, Noble Goals, Dedicated Doctors: The Story of Dalhousie Medical School (Nimbus, 2017), as a source for Dal Med Innovator profiles on historic figures.

Thanks as well to Moira Stewart for the national perspective, which relied on the published biography of Chester Stewart by Ross Langley, Medical Education and Health Research Innovator: Chester Bryant Stewart [1910-1999], MD, OC. Journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society, vol 14, 2011.

Recent News

- New global study Highlights the Biological Roots of Anxiety

- Dalhousie and NCIME launch first‑of‑its‑kind program in Membertou First Nation

- A message from Wanda M. Costen, PhD, Provost and Vice President Academic

- Rhodes scholar Sierra Sparks returns home to study medicine

- President Kim Brooks, Dr. Pat Croskerry appointed to Order of Canada

- Dal’s Highly Cited Researchers reflect on influential global research alliances

- A New Bursary Supporting Black Medical Students at Dalhousie

- Dalhousie’s first physician assistant cohort steps into Nova Scotia’s healthcare system