» Go to news main

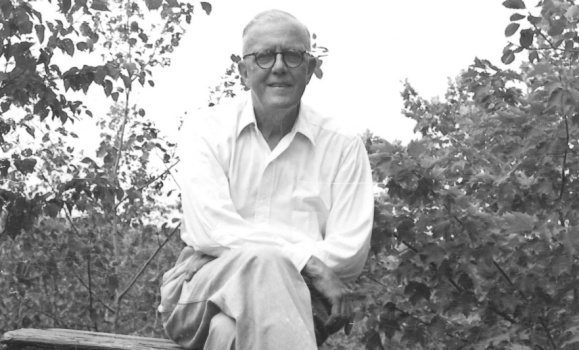

Dr. Benge Atlee: A revolutionary in maternal/newborn and women’s health

The Western world headed into the twentieth century on a tidal wave of unprecedented change.

In medicine, the almost-exclusively male establishment struggled to combine the new scientific rigour with leftover Victorian prudishness—particularly in the delicate area of women’s health. At the same time, women were beginning to wake to their own political power. This was the world that welcomed Harold Benge Atlee.

Atlee was born in his grandmother’s home in Pictou, Nova Scotia in 1890. From the start, he pushed the boundaries. He graduated from high school at 16 and immediately enrolled in medical school, becoming Dalhousie’s youngest-ever medical graduate at age 21. He later became the first head of Dalhousie’s Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, introducing many leading and sometimes-controversial practices.

“There’s no question some felt he was an upstart,” says Dr. Anthony Armson, Dalhousie Medical School’s recently retired head of Obstetrics & Gynecology. “He was one of those individuals… whenever there was an opportunity, he went after it.”

Dr. Atlee spent his first few years in medicine as a general practitioner in rural Nova Scotia, before joining a colleague in London, England for further medical training. With the arrival of war in Europe, however, Dr. Atlee joined the Royal Army Medical Corps, earning the Military Cross for valour.

Dr. Atlee returned to Halifax in 1921 to become the city’s only formally trained specialist in obstetrics and gynecology. The medical school’s dean, Dr. John Stewart, decided a fresh approach was needed at the just-built Grace Maternity Hospital and looked to Dr. Atlee.

At the time, the practice and teaching of women’s health was hampered by outdated notions of propriety which Dr. Atlee was given to ridiculing. As Dr. Jock Murray recounts in his 2017 book, Noble Goals, Dedicated Doctors, Atlee scoffed at his own education in obstetrics:

“The doctor who conducted the deliveries… a dear old fossil … did the job under the blankets… until finally, like a stage prestidigitator bringing a rabbit from a silk hat, he drew forth the baby and held it up for us to see. I shall never forget the prudish solemnity with which he crossed the room and said to us, ‘Gentlemen, that’s the proper way to deliver a child. A woman’s private parts should never be exposed to the male gaze.’”

In the face of the prevailing orthodoxy, Dr. Atlee’s appointment to head Dalhousie’s brand new Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology was not without controversy. A letter protesting his appointment—signed on behalf of the board of the Victoria General Hospital—was introduced in the provincial legislature. But Dean Stewart stuck to his guns and installed Atlee in 1923.

“To even suggest that obstetrics and gynecology should be a separate speciality was heretical in those days,” says Dr. Armson. “When Atlee started, obstetrics was primarily the domain of the midwife and deliveries were done in people’s homes. But that was a time in history when there was a general shift toward the hospital environment.”

Atlee became known as a skilled obstetrician and gynecological surgeon. To establish gynecology as a specialty apart from general surgery, he took the audacious approach of performing a general surgery procedure every time a general surgeon performed a gynecological procedure. His colleagues got the point and begrudgingly acknowledged his specialty.

Atlee’s pioneering techniques for vaginal hysterectomy led to fewer complications and shorter recovery times. In the delivery room, he replaced blankets and false modesty with candour and hands-on learning.

“It was less about the technology, less about the instruments,” says Dr. Armson. “Having facilities where women could undergo those procedures safely was a major part of it, yes, but at a certain point in societal development you make very small gains with technology. The big gains have been related to basic things.”

One of these simple yet important advances was Atlee’s insistence in the late 1920s that women get up and walking after delivery as soon as they were able. Previously, women were told to stay in bed for up to 12 days, robbing them of the chance to regain their strength.

The shift to hospital birth was not without false starts. Heavier and heavier anesthesia had led to doctors essentially pulling babies out of near-unconscious mothers. In the late 1930s, Atlee joined British physician Grantly Dick-Read (author of Natural Childbirth) in advocating a return to less-medicated births by preparing mothers for an active role in childbirth. Against the sentiment of his colleagues, he established a childbirth training clinic at the Grace. Women flocked to the clinic and an obstetrics revolution was born.

“The success (of childbirth training) was considerable in the majority of cases,” wrote Dr. Atlee at the time. “These women were very pleased and proud of the fact that they rather than the doctor had the baby, and that they were actually present at the event rather than drugged into unconsciousness.”

Atlee also promoted the then-unusual notion that birth was a family affair. By the 1950s, husbands were allowed to support their wives throughout the first stage of labour, mothers were encouraged to hold their babies immediately after birth, and older children were welcomed into the hospital to meet their new baby brothers and sisters.

It’s hard to overstate Dr. Atlee’s impact on how people are born in this country and on women’s health in general. By the time he passed away in 1978, maternal and infant mortality were a fraction of what they had been. Fittingly, the Nova Scotia Atlee Perinatal Database is named for him, and the endowment he left continues to fund his department’s research activities. And, his wisdom lives on through the annual Atlee Lecture.

“Dalhousie obstetrics and gynaecology is still highly regarded across the country and beyond. Many of the fundamental principles of the department are rooted in Atlee’s perspective,” says Dr. Armson. “In some ways he’s a mentor I never knew. I hold that kind of respect for him.”

Recent News

- New global study Highlights the Biological Roots of Anxiety

- Dalhousie and NCIME launch first‑of‑its‑kind program in Membertou First Nation

- A message from Wanda M. Costen, PhD, Provost and Vice President Academic

- Rhodes scholar Sierra Sparks returns home to study medicine

- President Kim Brooks, Dr. Pat Croskerry appointed to Order of Canada

- Dal’s Highly Cited Researchers reflect on influential global research alliances

- A New Bursary Supporting Black Medical Students at Dalhousie

- Dalhousie’s first physician assistant cohort steps into Nova Scotia’s healthcare system