News

» Go to news mainPainting a portrait of Alzheimer's disease

Dr. Mark Gilbert has experienced first-hand the healing power of art in end-of-life care.

The researcher and artist recalls his father Norman, an artist himself, painting portraits of his wife Pat (Gilbert’s mother), after she had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

“My father has been a professional artist for the past 70 years; he’s painted my mom hundreds of times,” says Dr. Gilbert. “About seven years ago, she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and he continued to paint her. There’s nothing about those pictures that explicitly describes the dementia, but once you know the context of what’s going on, it becomes not just a record of a husband and wife, but an incredibly intimate and moving record of a patient and their partner in care.”

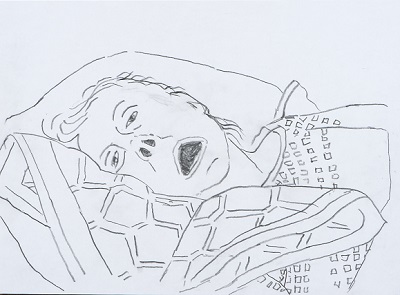

Pat later suffered a massive stroke from which she would not recover. Dr. Gilbert says he was “staggered” to discover that as his father kept vigil during what would be the last week of her life, he had brought his sketchbook to the hospital to continue drawing her.

Pat (I), Pencil on Paper, 2016. (Provided photo.)

Dr. Gilbert says the drawings of her final days made it easier for him and his father to discuss what could have been an uncomfortable subject. “Having the drawings as a means of engagement for us as a family meant that we talk more about my mom than we would have otherwise. My dad has said he cherishes the drawings because of that.”

Researching art and dementia

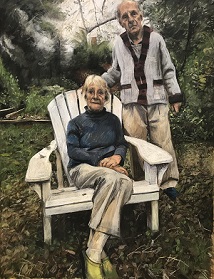

Based out of the Memory Clinic at the Camp Hill Veterans Memorial Building, Dr. Gilbert is continuing the work that previous artists have performed alongside Dr. Kenneth Rockwood of Dalhousie’s Division of Geriatric Medicine in using portraiture to explore the experiences of people living with dementia and their partners in care.

Consenting participants are introduced to Dr. Gilbert, who meets with them and begins the process of the portrait, while also collecting data for his shared qualitative research project with Dr. Rockwood.

“As well as working on the portrait, observing, interacting with the participants, I’m recording all the conversations that happen as part of the research process,” Dr. Gilbert explains. “All participants go through a follow-up semi-structured interview at the end of the study to ascertain their responses to the pictures and also the process of being drawn and painted.”

Mark Gilbert, Brian and Lindsay, Pastel on paper, 2018. (Provided photo).

The ongoing research study explores the relationships and interactions of patients and their partners in care attending the Memory Clinic.

Dr. Gilbert is giving a presentation at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia on Thursday, January 31 called Art & Dementia: The Paradox of Vulnerability, in which he’ll share stories from his more than 20 years of working with patients, physicians and caregivers on arts-based research projects in hospitals in North America and Europe.

“The theme of the talk is vulnerability,” says the native of Glasgow, Scotland. “The silence that occurs when working together can be seen as a vulnerable thing, but on the whole, the silence that happens is one of comfort. We actually know from previous studies that it can generate powerful reflective processes that can be potentially beneficial and can potentially be regarded as healing.

“There’s an intimacy that happens the minute you start a portrait of someone – but the portrait itself isn’t just made by me, it’s a collaboration. Patients usually see it as a testament to their own experience.”

Incorporating the humanities

Aside from his role at the hospital, Dr. Gilbert is a post-doctoral fellow in the Medical Humanities-HEALS program at Dalhousie Medical School. He’s worked with the program’s director, Dr. Wendy Stewart, to incorporate the humanities into the medical school curriculum.

“We worked to include humanities elements in Med 1 and 2 professional competencies case studies,” says Dr. Gilbert. “We continue to carry out workshops using the arts in all their forms to augment and foster critical thinking and open perspectives on end-of-life care.”

He describes working with young patients of Dr. Stewart’s with severe epilepsy, and their partners in care. The resulting artworks from that study were exhibited in Saint John, N.B. last year.

Mark Gilbert, Erin and Michaela, Pastel on paper, 2018. (Provided photo).

“That was an incredible experience of working with a vulnerable cohort of people. When you spend a great deal of time with them, you’re acutely aware of their vulnerabilities, but at the same time, from those vulnerabilities come amazing strength, from the children and their families.”

Dr. Gilbert envisions such art exhibitions as a way of engaging both the public and medical students.

“We’re also focusing on how we can use images such as these with medical students as a way of giving them a safe space to engage with sometimes challenging subject matter.”

While not a medical doctor (he earned a PhD in 2014 in the Medical Sciences Interdepartmental Area program at the University of Nebraska Medical Center), Dr. Gilbert is cognizant of the personal growth he’s experienced through his collaborations with patients, physicians and caregivers.

“Over the 20 years working in the field, I feel I’m much more empathetic, a much more compassionate person, not because I’m an artist, but because of the relationships I’ve formed through my work with medicine.”

Recent News

- New global study Highlights the Biological Roots of Anxiety

- Dalhousie and NCIME launch first‑of‑its‑kind program in Membertou First Nation

- A message from Wanda M. Costen, PhD, Provost and Vice President Academic

- Rhodes scholar Sierra Sparks returns home to study medicine

- President Kim Brooks, Dr. Pat Croskerry appointed to Order of Canada

- Dal’s Highly Cited Researchers reflect on influential global research alliances

- A New Bursary Supporting Black Medical Students at Dalhousie

- Dalhousie’s first physician assistant cohort steps into Nova Scotia’s healthcare system