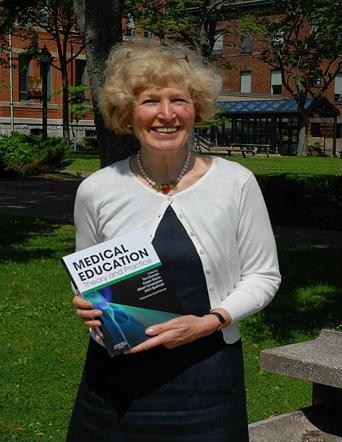

Dr. Karen Mann, medical education’s scholarly pioneer

In her late 60s, only a few years before she passed away, Dr. Karen Mann decided to take piano lessons. The Dalhousie medical educator had already been playing for years with the university’s choral group, but she still wanted to improve, to evolve. That same commitment to learning guided her through more than four decades of teaching, beyond her retirement years and up until her final day in November 2016.

“She didn’t really retire at all. Until her last day she was working full time,” says Dr. Joan Sargeant, her colleague for 20 years at Dalhousie. “Even though her post-retirement appointment at Dalhousie was only two days a week, she chose to work five.”

Dr. Mann made an enormous impact in her years at Dalhousie. She held 25 different positions, re-designed the medical school’s approach to training doctors, and helped establish medical education as a field of scholarly endeavour. In fact, she published dozens upon dozens of papers—so fervently that even in 2018, nearly two years after her passing, her research results are still coming out. Through it all, she helped fundamentally change how people around the world understood medical education as a profession and a practice.

She graduated from Dalhousie with a BSc in nursing in 1964 and, as a nurse, became fascinated with the process of educating patients about their own care. She was determined to figure out what worked and what didn’t, and to demonstrate the difference with scientific rigour. Her determination to push her research led her to earn a master’s in health education in 1978.

Mann focused her early research on patients with hypertension. Since it is a disease that presents few symptoms but is potentially deadly, hypertension provided the perfect test case for evaluating patient education techniques. Mann successfully defended her doctoral thesis on the topic in 1986. At that time, the job of director of Undergraduate Medical Education became available.

Mann focused her early research on patients with hypertension. Since it is a disease that presents few symptoms but is potentially deadly, hypertension provided the perfect test case for evaluating patient education techniques. Mann successfully defended her doctoral thesis on the topic in 1986. At that time, the job of director of Undergraduate Medical Education became available.

“When the position opened I went to the dean, Dr. Jock Murray," recalls Dr. Gray. "I said, ‘I know just the person for this vacancy’ and he hired her.”

Although medicine was well into “the modern era” by the mid-1980s, approaches to medical education lacked scientific rigour. Institutions had grown comfortable with existing models, which were built around lectures and practical exams. Dean Murray wanted to implement a pioneering approach being introduced elsewhere, known as “problem-based learning.” It would be Dr. Mann’s job to make it happen.

Under this model, instead of professors lecturing while students took notes, the professor would give the students a problem to solve. They would then work in groups to research the problem and return with a solution for the professor to critique.

Dr. Mann recognized that this model would provide medical students with the skills to gather up-to-date knowledge to treat difficult cases—a critical ability in times when the body of medical knowledge is growing too quickly for professors, physicians or students to keep pace.

“This was a great advance over a lecture-based curriculum, which teaches you four years of facts,” says Dr. Gray. “I can tell you that virtually everything I learned in medical school was obsolete within ten years of my graduation.”

Problem-based learning required instructors to take a completely different approach. Dr. Mann needed to convince a comfortable faculty that they needed to overhaul not just the content of their lectures, but their entire approach to medical education.

“A problem-based curriculum was constantly evolving, and so it took instructors a lot more time,” says Gray. “The faculty was reluctant to accept it at first, but Karen soldiered on and, with support from Jock Murray, it became a reality.”

Dr. Mann also championed medical education as a valid career path on its own. She helped negotiate a political thicket in convincing Acadia, Mount Saint Vincent and Dalhousie to develop a joint masters of medical education program in the late 1980s.

Dr. Mann also championed medical education as a valid career path on its own. She helped negotiate a political thicket in convincing Acadia, Mount Saint Vincent and Dalhousie to develop a joint masters of medical education program in the late 1980s.

In the mid-2000s she was heavily engaged in another interuniversity negotiation, this time to set the stage for an undergraduate medical program under the Dalhousie banner at the University of New Brunswick (officially launched in 2010 as Dalhousie Medicine New Brunswick). Dr. Sargeant believes Dr. Mann’s gentle persistence and passion for quality are what helped her navigate these tricky educational initiatives and their related political challenges.

Dr. Mann’s well-known kindness and willingness to engage people won her friends and collaborators across the globe. She held visiting professorships in places like Harvard, the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom and the International Medical University in Malaysia. To travel with her to a conference was to encounter a bewildering array of correspondents and colleagues.

“Folks from Hong Kong or Korea who she’d met at another conference would come and sit down and have a conversation with her and it was evident she had really influenced their lives,” Dr. Sargeant recalls. “We went to a number of conferences together and her calendar would be full of meetings to help people with their research or their education strategy.”

The long-term impact of an educator is hard to measure. Dr. Mann taught for more than 40 years, and is responsible for shaping hundreds of medical careers. Dr. Gray believes her impact will continue to be felt for a long time.

“In many respects she was even more important than the deans. Which sounds rather strange but she really did transform the medical education program at Dalhousie,” says Dr. Gray. “Virtually everyone who’s stepped into a major medical education administrative role in the last 10 to 15 years has been mentored by Karen.”

Recent News

- New global study Highlights the Biological Roots of Anxiety

- Dalhousie and NCIME launch first‑of‑its‑kind program in Membertou First Nation

- A message from Wanda M. Costen, PhD, Provost and Vice President Academic

- Rhodes scholar Sierra Sparks returns home to study medicine

- President Kim Brooks, Dr. Pat Croskerry appointed to Order of Canada

- Dal’s Highly Cited Researchers reflect on influential global research alliances

- A New Bursary Supporting Black Medical Students at Dalhousie

- Dalhousie’s first physician assistant cohort steps into Nova Scotia’s healthcare system