A physician’s greatest teacher

» Go to news mainClinical cadaver program at Dalhousie allows safe, realistic surgical simulation

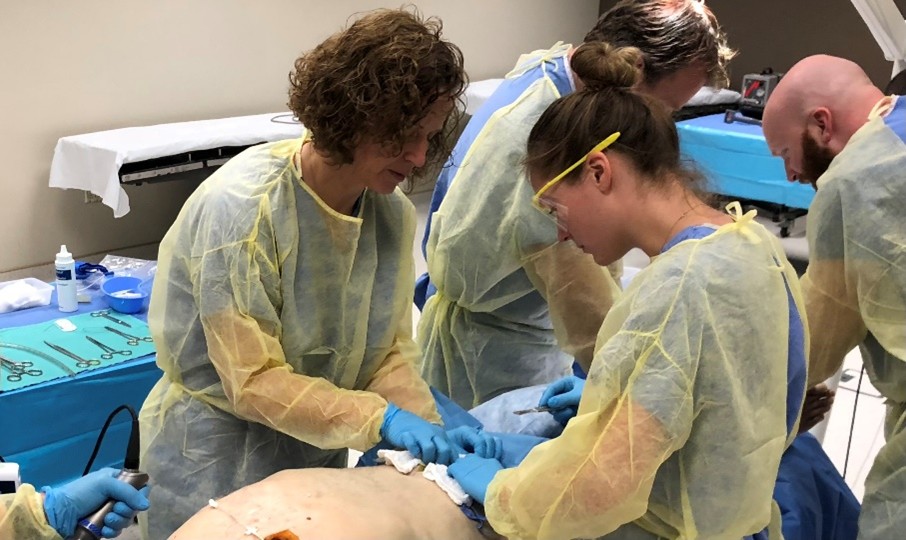

In a lab on the 14th floor of the Sir Charles Tupper Medical Building at Dalhousie University, four neatly prepared hospital beds await their next patients. These patients will not communicate what’s ailing them, nor react to a scalpel’s cut, or a needle’s prick. They can’t see, or breath. But because of them, countless lives will be saved.

These patients are clinical cadavers.

These patients are clinical cadavers.

Not unlike a living, breathing, human, cadavers have a story. Etched on their faces are traces of a life full of laughter, or in some cases, pain and illness. Though their hearts no longer beat, you cannot remove the traces of humanity.

In existence for more than 150 years, the Dalhousie University Human Body Donation Program accepts bodies from Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. These donations are critical to providing future healthcare practitioners with the knowledge they need to be successful in their careers.

Filling the gap

In 2006 while on a trip to Baltimore with colleague Dr. Adam Law, Dr. George Kovacs, current director of the Clinical Cadaver Program and emergency medicine physician, witnessed something that would forever change the way learners and physicians practiced on cadavers. In the basement of a hospital at the University of Maryland, he met Ron Wade, a Vietnam Vet and Director of the State Anatomy Board of Maryland. Each year in Maryland they prepare thousands of bodies to teach procedural skills. When Ron wheeled out the first cadaver, Dr. Kovacs was speechless.

“We were just so blown away by the fidelity of these cadavers,” he recalls. “All I could think about was the gap that's out there in terms of procedural learning.”

Until this point, cadavers were prepared traditionally with formaldehyde. The result was an extremely fixed material that does not move well. Traditional cadavers cannot be used to teach procedures and have typically been used for teaching relative anatomy.

It wasn’t long before Rob Sandeski, manager of Dalhousie’s Human Body Donation Program, was heading to Baltimore to learn the embalming techniques used by the Baltimore team. Trained as a funeral director and embalmer, Rob has now been caring for the deceased for more than 30 years. Upon his return to Halifax, he prepared the first donor, and with a few adjustments to the formula to allow for longevity, the Halifax Clinical Cadaver Preparation (Halifax Prep) was born.

The Halifax Prep

The first of its kind in Canada, and only the second place in North

The first of its kind in Canada, and only the second place in North America to utilize this method of preparing cadavers, the Halifax Prep allows the cadaver to be utilized for approximately eight weeks. Since developed, schools across Canada and in the United States have approached Dalhousie with requests to study and emulate the process. Despite this, Dalhousie remains one of the only places in the country using this method of cadaver preparation.

America to utilize this method of preparing cadavers, the Halifax Prep allows the cadaver to be utilized for approximately eight weeks. Since developed, schools across Canada and in the United States have approached Dalhousie with requests to study and emulate the process. Despite this, Dalhousie remains one of the only places in the country using this method of cadaver preparation.

With the updated method came the need for a place to practice. An old ambulance bay at the Halifax Infirmary was turned into a simulated resuscitation area, and with approval from the dean of the medical school, the Dalhousie Clinical Cadaver Program was formalized.

“It really was filling a gap and it did allow you to approach what scares you,” says Dr. Kovacs. “It allowed learners to do procedures that they just otherwise weren't going to have that opportunity to do unless they were lucky enough to have some sort of educational experience.”

Meaningful educational experiences

Dr. Anna MacLeod is Director of Education Research and Unit Head for Research in Medicine (RIM). She has been a social sciences researcher for over a decade, with the last five years spent researching the clinical cadaver program. She says of all the projects she’s ever worked on, nothing has captured her attention and interest from both an academic and personal perspective like this one.

“What was most striking was h ow deliberate, careful, and respectful the people are who work in the program,” she says. “And how committed they are not just to making sure that people's loved ones are treated with care and compassion, but also to make sure to offer a deeply engaging and meaningful educational experience.”

ow deliberate, careful, and respectful the people are who work in the program,” she says. “And how committed they are not just to making sure that people's loved ones are treated with care and compassion, but also to make sure to offer a deeply engaging and meaningful educational experience.”

There is a movement towards using high fidelity mannequins in the realm of education for simulation. These mannequins have been developed to reproduce humanness. What Dr. MacLeod and her research team have observed however, is that you simply cannot simulate the same reaction as with a clinical preparation.

“There's something irreplaceable about the humanity of the body that's there in front of you, whether it's a living body or not,” she says. “The fact that we've all had the shared experience of being alive, it does change how people respond to the task at hand.”

Dr. MacLeod has witnessed learners hold the hand of a cadaver during a difficult intubation, or ensure the draping remains over the body, showing respect the same way they would for a living patient.

“It's very touching to be in that space and observe how cadavers change the way that people practice.”

Transforming the Tupper

Since the first clinical preparation, the program has increased to accepting approximately 170 donors a year—a more than a 115 per cent per cent increase from 2006, with 60-70 per cent utilized for clinical procedural learning. A recently renovated lab in the Tupper Building is now the first in-house space designed specifically to accommodate clinical cadavers.

Since the first clinical preparation, the program has increased to accepting approximately 170 donors a year—a more than a 115 per cent per cent increase from 2006, with 60-70 per cent utilized for clinical procedural learning. A recently renovated lab in the Tupper Building is now the first in-house space designed specifically to accommodate clinical cadavers.

“This space has been a big piece of Dal taking ownership of a space that's theirs because the cadaver program is theirs, the human body donation program is theirs,” says Dr. Kovacs. “This allows increased access for this type of programming that's in demand for every type of user.”

The new lab provides further opportunities for learning for undergraduate and postgraduate students, as well as for faculty and external groups.

Rob says in any given week there might be paramedic students, specialized RCMP, residents, surgeons and other health care providers, all utilizing the new space, all practicing to save lives.

“An orthopedic surgeon who came in recently had a patient with a pelvic tumour,” recalls Rob. “He and another surgeon came to review and perform that surgery on our donor before they were to perform it on the living patient. This gave them the ability to discuss the location of the tumor and anatomy of this area before going into the operating room. It is these opportunities in which improve patient safety, whoever that patient is, they’re going to benefit from that practice.”

Saving lives

Eighteen years after the inception of the Halifax Preparation, more than 2100 donations have been made to the Human Body Donation Program, providing learning opportunities for countless undergraduate, postgraduate, continuing medical education, and other groups.

Dr. Kovacs, who has been involved in the program since its inception, continues to remark of the humbling experience it is working with cadavers.

“It is such a privilege to interact with them,” he says. “They have been, and continue to be, my greatest teachers. These people have saved more lives than I ever will as an emergency physician.”

Recent News

- New global study Highlights the Biological Roots of Anxiety

- Dalhousie and NCIME launch first‑of‑its‑kind program in Membertou First Nation

- A message from Wanda M. Costen, PhD, Provost and Vice President Academic

- Rhodes scholar Sierra Sparks returns home to study medicine

- President Kim Brooks, Dr. Pat Croskerry appointed to Order of Canada

- Dal’s Highly Cited Researchers reflect on influential global research alliances

- A New Bursary Supporting Black Medical Students at Dalhousie

- Dalhousie’s first physician assistant cohort steps into Nova Scotia’s healthcare system